Executables and Processes

From a user's perspective, the main purpose of the computing system is to run applications. Applications are used for the user's benefit: listen to music, organize files, play games, develop applications, chat over the Internet, etc.

A running application is called a process. A user starts a process, interacts with a process, ends a process.

When a process runs for the benefit of the user, it executes instructions that operate on data. These two items (executing instructions and operating on data) are the most relevant items to understanding processes and executables. Instructions, also called code, and data reside in memory. Code is read from memory by the processor / CPU (Central Processing Unit), then it is decoded and interpreted by the CPU, then it is executed on data that is also read from memory by the CPU. Finally, the result of the operation is stored back into memory. So, each process has its memory space that stores code and data.

TODO: diagram with memory (code, data) and CPU interaction

We say that each process has its own memory space, also called address space.

We refer to this as process address space, or process virtual address space ((P)VAS) (why this is named virtual is outside the scope of this section).

This space is populated with data and code.

Data is dynamic with respect to contents and size: it can be modified, it can be enlarged or shrinked.

Code is static: it can't be (easily) modified, it can't be (easily) enlarged.

Data can be read from or written to outside the process memory, to outside devices (I/O - Input/Output) - keyboard, monitor, network, disk.

Code is however read at process birth time.

The origin of the code and some parts of the data is the application executable (or program executable). The application executable is a binary file with a given format that stores the code and initial data that will be used to set up the process. The birth of a process means loading the code and initial data from the program executable into memory. This creates the process virtual address space. Then the CPU is pointed to execute instructions from the new process virtual address spaces and now the process is running.

TODO: diagram with executable (code, data) and process memory (code, data) + CPU (code + data interaction) + I/O (for parts of data)

We call the starting of a process from a program executable loading. The loader is the piece of software responsible for this. Whatever happens during loading is said to happen during load-time. After the process starts, whatever happens is said to happen at / during runtime.

For this session we will first look at the process virtual address space and see how it is updated at runtime. We will then map that information to the program executable and what's hapenning at load-time. We will then spend more time dissecting and executable and make the first steps on static analysis, the subject of the next section.

Process Memory Layout

To understand the full picture of program execution it is vital to understand the memory layout of processes from ELF executables.

The kernel provides an interface in /proc/<PID>/maps for each process to see how the memory layout looks like.

Let's write a simple Hello World application and investigate.

IMPORTANT: Note that we have removed Address Space Layout Randomization for these examples. We'll explain this later.

#include <stdio.h>

int main()

{

printf("Hello world\n");

malloc(10000);

while(1){

;

}

return 0;

}

$ gcc -Wall hw.c -o hw -m32

$ ./hw &

[1] 4771

Hello world

$ cat /proc/4771/maps

08048000-08049000 r-xp 00000000 08:06 1843771 /tmp/hw

08049000-0804a000 r--p 00000000 08:06 1843771 /tmp/hw

0804a000-0804b000 rw-p 00001000 08:06 1843771 /tmp/hw

0804b000-0806e000 rw-p 00000000 00:00 0 [heap]

f7ded000-f7dee000 rw-p 00000000 00:00 0

f7dee000-f7f93000 r-xp 00000000 08:06 917808 /lib32/libc-2.17.so

f7f93000-f7f95000 r--p 001a5000 08:06 917808 /lib32/libc-2.17.so

f7f95000-f7f96000 rw-p 001a7000 08:06 917808 /lib32/libc-2.17.so

f7f96000-f7f99000 rw-p 00000000 00:00 0

f7fd9000-f7fdb000 rw-p 00000000 00:00 0

f7fdb000-f7fdc000 r-xp 00000000 00:00 0 [vdso]

f7fdc000-f7ffc000 r-xp 00000000 08:06 917869 /lib32/ld-2.17.so

f7ffc000-f7ffd000 r--p 0001f000 08:06 917869 /lib32/ld-2.17.so

f7ffd000-f7ffe000 rw-p 00020000 08:06 917869 /lib32/ld-2.17.so

fffdd000-ffffe000 rw-p 00000000 00:00 0 [stack]

If we start another process in the background the output for it will be exactly the same as this one. Why is that? The answer, of course, is virtual memory. The kernel provides this mechanism through which each process has an address space completely isolated from that of other running processes. They can still communicate using inter-process communication mechanisms provided by the kernel but we won't get into that here. Shortly put, there would be two processes with the same name and with two apparently identical mappings, but still the two programs would be isolated from one another.

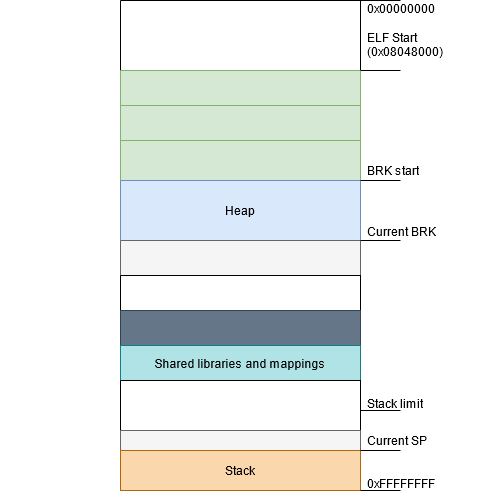

An initial schematic of the memory layout would be the following:

Executable

As we have seen, there are three memory regions associated with the executable:

08048000-08049000 r-xp 00000000 08:06 1843771 /tmp/hw

08049000-0804a000 r--p 00000000 08:06 1843771 /tmp/hw

0804a000-0804b000 rw-p 00001000 08:06 1843771 /tmp/hw

From their permissions we can infer what they correspond to:

08048000-08049000 r-xpis the.textsection along with the rest of the executable parts08049000-0804a000 r–pis the.rodatasection0804a000-0804b000 rw-pconsists of the.data,.bsssections and other R/W sections

It is interesting to note that the executable is almost identically mapped into memory.

The only region that is compressed in the binary is the .bss section.

Let's see this in action by dumping the header of the file:

$ hexdump -Cv hw | head

00000000 7f 45 4c 46 01 01 01 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 |.ELF............|

00000010 02 00 03 00 01 00 00 00 b0 83 04 08 34 00 00 00 |............4...|

00000020 78 11 00 00 00 00 00 00 34 00 20 00 0a 00 28 00 |x.......4. ...(.|

00000030 1e 00 1b 00 06 00 00 00 34 00 00 00 34 80 04 08 |........4...4...|

00000040 34 80 04 08 40 01 00 00 40 01 00 00 05 00 00 00 |4...@...@.......|

00000050 04 00 00 00 03 00 00 00 74 01 00 00 74 81 04 08 |........t...t...|

00000060 74 81 04 08 13 00 00 00 13 00 00 00 04 00 00 00 |t...............|

00000070 01 00 00 00 01 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 80 04 08 |................|

00000080 00 80 04 08 6c 06 00 00 6c 06 00 00 05 00 00 00 |....l...l.......|

00000090 00 10 00 00 01 00 00 00 00 0f 00 00 00 9f 04 08 |................|

$ gdb ./hw

gdb-peda$ hexdump 0x08048000 /10

0x08048000 : 7f 45 4c 46 01 01 01 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 .ELF............

0x08048010 : 02 00 03 00 01 00 00 00 b0 83 04 08 34 00 00 00 ............4...

0x08048020 : 78 11 00 00 00 00 00 00 34 00 20 00 0a 00 28 00 x.......4. ...(.

0x08048030 : 1e 00 1b 00 06 00 00 00 34 00 00 00 34 80 04 08 ........4...4...

0x08048040 : 34 80 04 08 40 01 00 00 40 01 00 00 05 00 00 00 4...@...@.......

0x08048050 : 04 00 00 00 03 00 00 00 74 01 00 00 74 81 04 08 ........t...t...

0x08048060 : 74 81 04 08 13 00 00 00 13 00 00 00 04 00 00 00 t...............

0x08048070 : 01 00 00 00 01 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 80 04 08 ................

0x08048080 : 00 80 04 08 6c 06 00 00 6c 06 00 00 05 00 00 00 ....l...l.......

0x08048090 : 00 10 00 00 01 00 00 00 00 0f 00 00 00 9f 04 08 ................

Heap

The heap comes right after the executable at 0x0804b000 and ends at 0x0806e000 which is the current brk point.

The memory allocator will increase the brk when more allocations are made but will not decrease it when memory is freed so as to reuse the memory regions for future allocations.

The allocator in libc actually keeps a list of past allocations and their sizes.

When future allocations will require the same size as a previously freed region, the allocator will reuse one from this lookup table.

The process is called binning.

Let's see how the brk evolves in our executable using strace:

$ strace -i -e brk ./hw

[ Process PID=1995 runs in 32 bit mode. ]

[f7ff2314] brk(0) = 0x804b000

Hello world

[f7fdb430] brk(0) = 0x804b000

[f7fdb430] brk(0x806e000) = 0x806e000

Let's test the fact that the brk does not decrease and that future malloc calls can reuse previously freed regions:

#include <stdio.h>

int main()

{

void * buf[15];

int i;

for( i = 0 ; i < 15; i++)

buf[i] = malloc( i * 100) ;

for( i = 0 ; i < 15; i++)

free( buf[i] );

for( i = 0 ; i < 15; i++)

buf[i] = malloc( i * 100) ;

return 0;

}

$ strace -e brk ./hw

[ Process PID=2424 runs in 32 bit mode. ]

brk(0) = 0x804b000

brk(0) = 0x804b000

brk(0x806c000) = 0x806c000

+++ exited with 0 +++

$ ltrace -e malloc ./hw

hw->malloc(0) = 0x804b008

hw->malloc(100) = 0x804b018

hw->malloc(200) = 0x804b080

hw->malloc(300) = 0x804b150

hw->malloc(400) = 0x804b280

hw->malloc(500) = 0x804b418

hw->malloc(600) = 0x804b610

hw->malloc(700) = 0x804b870

hw->malloc(800) = 0x804bb30

hw->malloc(900) = 0x804be58

hw->malloc(1000) = 0x804c1e0

hw->malloc(1100) = 0x804c5d0

hw->malloc(1200) = 0x804ca20

hw->malloc(1300) = 0x804ced8

hw->malloc(1400) = 0x804d3f0

hw->malloc(0) = 0x804b008

hw->malloc(100) = 0x804b018

hw->malloc(200) = 0x804b080

hw->malloc(300) = 0x804b150

hw->malloc(400) = 0x804b280

hw->malloc(500) = 0x804b418

hw->malloc(600) = 0x804b610

hw->malloc(700) = 0x804b870

hw->malloc(800) = 0x804bb30

hw->malloc(900) = 0x804be58

hw->malloc(1000) = 0x804c1e0

hw->malloc(1100) = 0x804c5d0

hw->malloc(1200) = 0x804ca20

hw->malloc(1300) = 0x804ced8

hw->malloc(1400) = 0x804d3f0

+++ exited (status 0) +++

As you can see, only one brk call is made.

Furthermore, after the regions are freed they are reused.

IMPORTANT: This behaviour of the allocator is important in the Use After Free class of vulnerabilities which we will be covering in the next labs.

Memory Mappings and Libraries

In our example we had the following memory mappings:

f7ded000-f7dee000 rw-p 00000000 00:00 0

f7dee000-f7f93000 r-xp 00000000 08:06 917808 /lib32/libc-2.17.so

f7f93000-f7f95000 r--p 001a5000 08:06 917808 /lib32/libc-2.17.so

f7f95000-f7f96000 rw-p 001a7000 08:06 917808 /lib32/libc-2.17.so

f7f96000-f7f99000 rw-p 00000000 00:00 0

f7fd9000-f7fdb000 rw-p 00000000 00:00 0

f7fdb000-f7fdc000 r-xp 00000000 00:00 0 [vdso]

f7fdc000-f7ffc000 r-xp 00000000 08:06 917869 /lib32/ld-2.17.so

f7ffc000-f7ffd000 r--p 0001f000 08:06 917869 /lib32/ld-2.17.so

f7ffd000-f7ffe000 rw-p 00020000 08:06 917869 /lib32/ld-2.17.so

All functions that are called from external libraries pull in the whole library into the address space. As these are also ELF files you can see that they have similar patterns: multiple sections with different permissions just like the main executable.

One more thing to note here is that large calls to malloc result in calls to mmap2:

#include <stdio.h>

int main()

{

printf("Hello world\n");

printf("Small allocation %p\n", malloc(10000));

printf("Big allocation %p\n", malloc(10000000));

return 0;

}

# strace -e brk,mmap2 ./hw_large

[ Process PID=3445 runs in 32 bit mode. ]

brk(0) = 0x804b000

mmap2(NULL, 4096, PROT_READ|PROT_WRITE, MAP_PRIVATE|MAP_ANONYMOUS, -1, 0) = 0xfffffffff7fda000

mmap2(NULL, 265183, PROT_READ, MAP_PRIVATE, 3, 0) = 0xfffffffff7f99000

mmap2(NULL, 1747628, PROT_READ|PROT_EXEC, MAP_PRIVATE|MAP_DENYWRITE, 3, 0) = 0xfffffffff7dee000

mmap2(0xf7f93000, 12288, PROT_READ|PROT_WRITE, MAP_PRIVATE|MAP_FIXED|MAP_DENYWRITE, 3, 0x1a5000) = 0xfffffffff7f93000

mmap2(0xf7f96000, 10924, PROT_READ|PROT_WRITE, MAP_PRIVATE|MAP_FIXED|MAP_ANONYMOUS, -1, 0) = 0xfffffffff7f96000

mmap2(NULL, 4096, PROT_READ|PROT_WRITE, MAP_PRIVATE|MAP_ANONYMOUS, -1, 0) = 0xfffffffff7ded000

mmap2(NULL, 4096, PROT_READ|PROT_WRITE, MAP_PRIVATE|MAP_ANONYMOUS, -1, 0) = 0xfffffffff7fd9000

Hello world

brk(0) = 0x804b000

brk(0x806e000) = 0x806e000

Small allocation 0x804b008

mmap2(NULL, 10002432, PROT_READ|PROT_WRITE, MAP_PRIVATE|MAP_ANONYMOUS, -1, 0) = 0xfffffffff7463000

Big allocation 0xf7463008

As expected, the brk is increased when the first allocation is made.

However, larger regions are backed by memory mappings.

Stack

If you observed from previous traces, the mmap2 call returns addresses towards NULL (lower addresses).

It behaves like this because there is another important memory region called the stack that has a fixed size: usually 8 MB.

Since the heap and the mmap region do not have this limit imposed the optimization is to start mappings from a known boundary: the stack end boundary.

Let's put this into perspective.

You can view the current stack limit using ulimit -s.

$ ulimit -s

8192

$ python

>>> hex(0xffffffff - 8192*1024)

'0xff7fffff'

This address is the stack boundary.

It seems odd then that the first mmap in the program above ends at 0xf7ffe000 and not 0xff7fffff.

This is probably an optimization.

However, we can set the stack size to unlimited and the mmap allocation direction will reverse:

$ ulimit -s unlimited

$ strace -e mmap2,brk ./hw_large

[ Process PID=4617 runs in 32 bit mode. ]

brk(0) = 0x804b000

mmap2(NULL, 4096, PROT_READ|PROT_WRITE, MAP_PRIVATE|MAP_ANONYMOUS, -1, 0) = 0x55578000

mmap2(NULL, 265183, PROT_READ, MAP_PRIVATE, 3, 0) = 0x55579000

mmap2(NULL, 1747628, PROT_READ|PROT_EXEC, MAP_PRIVATE|MAP_DENYWRITE, 3, 0) = 0x555ba000

mmap2(0x5575f000, 12288, PROT_READ|PROT_WRITE, MAP_PRIVATE|MAP_FIXED|MAP_DENYWRITE, 3, 0x1a5000) = 0x5575f000

mmap2(0x55762000, 10924, PROT_READ|PROT_WRITE, MAP_PRIVATE|MAP_FIXED|MAP_ANONYMOUS, -1, 0) = 0x55762000

mmap2(NULL, 4096, PROT_READ|PROT_WRITE, MAP_PRIVATE|MAP_ANONYMOUS, -1, 0) = 0x55765000

mmap2(NULL, 4096, PROT_READ|PROT_WRITE, MAP_PRIVATE|MAP_ANONYMOUS, -1, 0) = 0x55579000

Hello world

brk(0) = 0x804b000

brk(0x806e000) = 0x806e000

Small allocation 0x804b008

mmap2(NULL, 10002432, PROT_READ|PROT_WRITE, MAP_PRIVATE|MAP_ANONYMOUS, -1, 0) = 0x55766000

Big allocation 0x55766008

^Z

[1]+ Stopped strace -e mmap2,brk ./hw_large

$ cat /proc/4617/maps

08048000-08049000 r-xp 00000000 08:06 1843771 /tmp/hw_large

08049000-0804a000 r--p 00000000 08:06 1843771 /tmp/hw_large

0804a000-0804b000 rw-p 00001000 08:06 1843771 /tmp/hw_large

0804b000-0806e000 rw-p 00000000 00:00 0 [heap]

55555000-55575000 r-xp 00000000 08:06 917869 /lib32/ld-2.17.so

55575000-55576000 r--p 0001f000 08:06 917869 /lib32/ld-2.17.so

55576000-55577000 rw-p 00020000 08:06 917869 /lib32/ld-2.17.so

55577000-55578000 r-xp 00000000 00:00 0 [vdso]

55578000-5557a000 rw-p 00000000 00:00 0

555ba000-5575f000 r-xp 00000000 08:06 917808 /lib32/libc-2.17.so

5575f000-55761000 r--p 001a5000 08:06 917808 /lib32/libc-2.17.so

55761000-55762000 rw-p 001a7000 08:06 917808 /lib32/libc-2.17.so

55762000-560f0000 rw-p 00000000 00:00 0

fffdd000-ffffe000 rw-p 00000000 00:00 0 [stack]

As you can see, the big allocation is now towards the stack instead of towards the heap.

Returning to the main functionality of the stack, remember from the previous lab that local variables are declared on the stack. This translates into assembly code in the following way:

int main()

{

char buf[1000];

int i;

............

}

The C snippet would be translated into ASM something like:

0804840c <main>:

804840c: 55 push ebp

804840d: 89 e5 mov ebp,esp

804840f: 81 ec f0 03 00 00 sub esp,0x3f0

..........

The 0x3f0 hex value is equal to 1008 in decimal, which is precisely 1000 (from buf) + 4 (from i) + 4 (the storage of another int that the compiler used later in the code).

As the program subtracts more from esp the kernel will provide pages on-demand until the stack boundary or another mmap-ing is hit.

The kernel will, in this case, kill the application because of the Segmentation Fault.

Segmentation Fault

Now that we know everything about the memory address space we can say more about the infamous Segmentation Fault that all of us have, at some time, encountered.

It is basically a permission violation.

Apart from the mappings that appear in /proc/<PID>/maps with r--, rw-, etc, you can consider that everything else is ---.

Thus, a read access at such a location will violate the permission of that region so the whole app will be killed by the signal received (unless it has a signal handler).

Examples:

- Dereferencing a

NULLpointer will try to read from0x00000000which is not (usually) mapped =>SIGSEGV(read access on none) - Writing after the end of a heap buffer (if the heap buffer is exactly at the end of a mapping) will determine writes into unmapped pages =>

SIGSEGV(write access on none) - Trying to write to

.rodata=>SIGSEGV(write access on read only) - Overwriting the stack with

"AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAA"will also overwrite the return address and make the execution go to0x41414141=>SIGSEGV(execute access on none) - Overwriting the stack and return address with another address to a shellcode on the stack =>

SIGSEGV(execute access on read/write only) - Trying to rewrite the binary (

int *v = main; *v = 0x90909090;) =>SIGSEGV(write access on read/execute only)

Tutorials

This session is focused on the transformation of an ELF file (stored on disk) as it is loaded into memory and becomes a process (stored into memory). We will first analyze the structure of an ELF file and how this structure evolves when going from C source code, to object file and then to either an executable or a shared library. We will also skim over how various elements are interpreted by the linker and the loader. Finally, we will see the layout of a process once it is loaded into memory.

Big Picture View

Sun Microsystems' SunOS came up with the concept of dynamic shared libraries and introduced it to UNIX in the late 1980s.

UNIX System V Release 4, which Sun co-developed, introduced the ELF object format adaptation from the Sun scheme.

Later it was developed and published as part of the ABI (Application Binary Interface) as an improvement over COFF, the previous object format and by the late 1990s it had become the standard for UNIX and UNIX-like systems including Linux and BSD derivatives.

Depending on processor architectures, several specifications have emerged with minor changes, but for this session we will be focusing on the ELF-32 format.

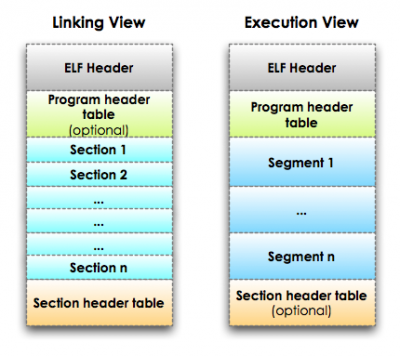

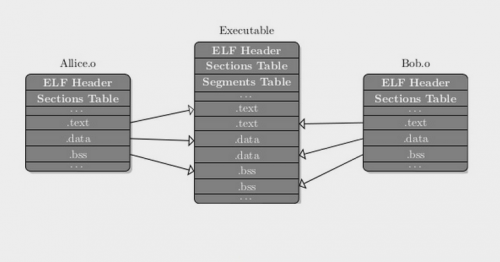

The structure of an ELF file during the linking process is the same with that of an object file. The linking process involves collecting and combining code and data into a single file that will later be loaded into memory and executed. On the right hand side we can see how the the ELF file structure will be transformed in memory. Sections instruct the Linker while Segments instruct the Operating System.

As we can see, the information inside the two program headers and the section headers gets merged as needed inside the more familiar program segments. The basic role of the ELF file format is to serve as a roadmap for the linker and the OS Loader to generate a running process.

Static/Dynamic linking

Out of practical considerations, for very large programs, even early on, it was very impractical to store all of the source code inside a single file.

One of the most mundane of all actions, namely splitting your source code into functions across multiple files while still obtaining a valid running program was a difficult engineering challenge.

The initial paradigm was called static linking and was the only option inside the COFF file format.

It involves interpreting each piece of code from each file and then merging all the information inside a single binary that would contain all the machine code necessary for the program.

This way of doing things, still in use today, involves loading all of the code and data into memory regardless of use case.

This basically meant that, the required resources to run a program were determined by the number of instances, with no possibility of optimization.

Running 10 instances of the same program meant that there was a lot of code duplication going on in the memory space.

Along with the ELF format came a new way of doing things.

Instead of linking all the source files that contained subroutines into the final binaries, separate binaries were organized in libraries that could be loaded per use case, on demand.

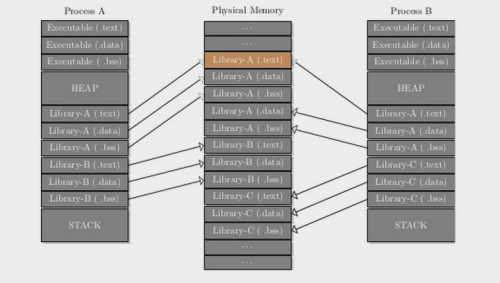

Essentially, the libraries were loaded only once into memory and when a program instance required a subroutine from a specific library it would inquire a special OS component about it and new resources would be allocated only for the volatile parts of the library image (.bss and .data).

The new process allowed for a much more efficient resource utilization and was named dynamic linking and the new type of library files were called shared objects.

Running 10 instances of the same program now meant that only the volatile parts of those binaries would be duplicated.

In cases where the same code can be reused, it is allocated only once and used by multiple instances of the same program.

ELF Types

There are several ELF types but the most common types we will be dealing with are:

- Relocatable Files

- Shared Objects

- Executable Files

ELF Type - Relocatable Files

Relocatable files are obtained using the core compiler and basically contain all the ELF information necessary except for data like external variables or subroutines that are present in other files.

gcc -c -o reloc.o source.c

gcc -c -fPIC -o reloc.o source.c

The first command will produce a relocatable file that will later constitute an executable or a static library. If we want to use the relocatable file to later create a shared library we need to use the second variant to create a relocatable file that has Position Independent Code (PIC).

ELF Type - Shared Objects

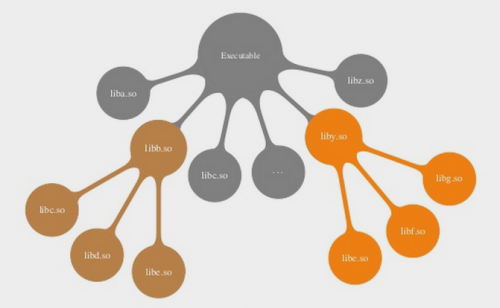

Shared libraries are loaded up at runtime as needed by an OS component named the dynamic loader. Shared objects may include other shared objects and this aspect is very important because, when loading specific subroutines, the ELF file must provide its dependencies. As such, the process of dynamic linking does a breadth first search gradually building the full dependency list.

You can view the list of shared object dependencies for any given binary as well as the addresses where they will be loaded in memory by using the ldd command.

ldd /bin/ls

linux-gate.so.1 => (0x00e02000)

librt.so.1 => /lib/tls/i686/cmov/librt.so.1 (0x004f9000)

libselinux.so.1 => /lib/libselinux.so.1 (0x00c62000)

libacl.so.1 => /lib/libacl.so.1 (0x00a87000)

libc.so.6 => /lib/tls/i686/cmov/libc.so.6 (0x00110000)

libpthread.so.0 => /lib/tls/i686/cmov/libpthread.so.0 (0x00325000)

/lib/ld-linux.so.2 (0x00a45000)

libdl.so.2 => /lib/tls/i686/cmov/libdl.so.2 (0x0077d000)

libattr.so.1 => /lib/libattr.so.1 (0x00dd7000)

All libraries should adhere to a strict naming convention. Shared objects have two names:

soname- that consists of the prefixlib, followed by the library name, then a.so, another dot, then the major version (e.g.libtest.so.1)- real name - is actually a filename, that usually extends the

sonameby adding a dot and minor version number along with the release version (e.g.libtest.so.1.23.3)

Additionally, each library source file should have an accompanying header file with the extension .h and the same name.

Adhering to these naming conventions is quite important as dependencies are resolved based on the soname.

gcc -c -fPIC libtesting.c

ld -shared -soname libtesting.so.1 -o libtesting.so.1.0 -lc libtesting.o

ldconfig -v -n .

ln -sf libtesting.so.1 libtesting.so

export LD_LIBRARY_PATH=.:"$LD_LIBRARY_PATH"

gcc -o main_program main_program.c -L. -ltesting

The first line creates an object file with position independent code.

The second line will create the shared object with soname libtesting.so.1 and a real filename of libtesting.so.1.0 by using the linker.

Shared objects are usually installed in other directories but the line containing ldconfig, will install it in the current directory.

At runtime the standard directories like /usr/lib are searched, but we add the local directory to the search path by modifying the LD_LIBRARY_PATH environment variable.

Finally, the executable is created by dynamic linking against the shared object.

A good tutorial on how to create a basic shared object can be found here.

ELF Type - Executable Files

They are regarded as the end result and contain all the information necessary to create a running process.

ELF Structure

The following wiki sections on ELF structure are dense and are not meant to be known by heart. Do not try to read them all at once and memorize them, but rather use the following chapters as reference.

Tools of the trade are:

readelfobjdumpldd- Ghidra/IDA (Ghidra is Open Source, while IDA is not and it is really expensive)

The command outputs that follow are rather large so we will only be discussing the less obvious parts. We will also leave out information that's not really that important or generally weird.

ELF Header

Using readelf is straight-forward enough:

readelf -h program

ELF Header:

Magic: 7f 45 4c 46 01 01 01 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00

Class: ELF32

Data: 2's complement, little endian

Version: 1 (current)

OS/ABI: UNIX - System V

ABI Version: 0

Type: EXEC (Executable file)

Machine: Intel 80386

Version: 0x1

Entry point address: 0x8048330

Start of program headers: 52 (bytes into file)

Start of section headers: 4392 (bytes into file)

Flags: 0x0

Size of this header: 52 (bytes)

Size of program headers: 32 (bytes)

Number of program headers: 8

Size of section headers: 40 (bytes)

Number of section headers: 30

Section header string table index: 27

Below we will discuss the less evident aspects of the above output

- Elf Identification (16 bytes)

- Magic - the first bytes of the binary that identify the file as ELF

- Class - identifies the type of ELF (ex: ELF-32, ELF-64)

- Data - specifies the type of data encoding

- Version - version of the ELF header

- OS/ABI - version of the OS

- ABI - version of the ABI specification

- Type - Relocatable, Executable, Shared Object

- Machine - Required Machine architecture to run the executable

- Entry Point Address - the memory address where the OS loader transfers control to the process code for the first time.

- Start of Program Headers - File offset where the array of program headers start

- Start of Section Headers - File offset where the array of section headers starts

- Section Header String Table Index - the index in the section table name where the information about the section name string table can be found

Program Headers

Program Headers are only present inside Executable and Shared Object files.

Again, readelf is used with minimum syntax:

$ readelf -l program

Elf file type is EXEC (Executable file)

Entry point 0x8048330

There are 8 program headers, starting at offset 52

Program Headers:

Type Offset VirtAddr PhysAddr FileSiz MemSiz Flg Align

PHDR 0x000034 0x08048034 0x08048034 0x00100 0x00100 R E 0x4

INTERP 0x000134 0x08048134 0x08048134 0x00013 0x00013 R 0x1

[Requesting program interpreter: /lib/ld-linux.so.2]

LOAD 0x000000 0x08048000 0x08048000 0x004e4 0x004e4 R E 0x1000

LOAD 0x000f0c 0x08049f0c 0x08049f0c 0x00108 0x00110 RW 0x1000

DYNAMIC 0x000f20 0x08049f20 0x08049f20 0x000d0 0x000d0 RW 0x4

NOTE 0x000148 0x08048148 0x08048148 0x00044 0x00044 R 0x4

GNU_STACK 0x000000 0x00000000 0x00000000 0x00000 0x00000 RW 0x4

GNU_RELRO 0x000f0c 0x08049f0c 0x08049f0c 0x000f4 0x000f4 R 0x1

Section to Segment mapping:

Segment Sections...

00

01 .interp

02 .interp .note.ABI-tag .note.gnu.build-id .hash .gnu.hash .dynsym .dynstr .gnu.version .gnu.version_r .rel.dyn .rel.plt .init .plt .text .fini .rodata .eh_frame

03 .ctors .dtors .jcr .dynamic .got .got.plt .data .bss

04 .dynamic

05 .note.ABI-tag .note.gnu.build-id

06

07 .ctors .dtors .jcr .dynamic .got

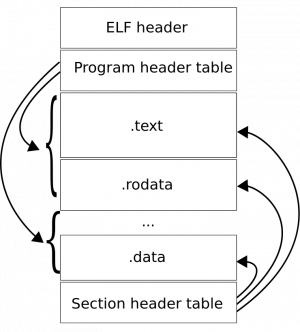

The Program Header table features an array of structures that shows how parts of the file will be mapped into memory at runtime. The last parts of the output show what sections will be merged into various program headers before loading the ELF into memory and becoming segments.

TypePHDR- information about the program header table itselfINTERP- information about the null terminated string that specifies the path to the dynamic loader. This header is only present in executable that use shared object codeLOAD- use to specify a general purpose loadable segmentDYNAMIC- information necessary to the dynamic linking process

Offset- offset from the beginning of the file where the segment beginsVirtAddr- the address where the segment will start in memoryFileSz- number of bytes occupied by the segment on diskMemSiz- number of bytes occupied by the segment in memoryAlign- specifies a boundary to which the segments are aligned on file and in memory

Here are two resources to read about GNU_RELRO and GNU_STACK Program Headers.

Section Table

Section headers are the central piece of reference used to organize the ELF files both on disk and in memory.

readelf -S program

There are 30 section headers, starting at offset 0x1128:

Section Headers:

[Nr] Name Type Addr Off Size ES Flg Lk Inf Al

[ 0] NULL 00000000 000000 000000 00 0 0 0

[ 1] .interp PROGBITS 08048134 000134 000013 00 A 0 0 1

[ 2] .note.ABI-tag NOTE 08048148 000148 000020 00 A 0 0 4

[ 3] .note.gnu.build-i NOTE 08048168 000168 000024 00 A 0 0 4

[ 4] .hash HASH 0804818c 00018c 000028 04 A 6 0 4

[ 5] .gnu.hash GNU_HASH 080481b4 0001b4 000020 04 A 6 0 4

[ 6] .dynsym DYNSYM 080481d4 0001d4 000050 10 A 7 1 4

[ 7] .dynstr STRTAB 08048224 000224 00004c 00 A 0 0 1

[ 8] .gnu.version VERSYM 08048270 000270 00000a 02 A 6 0 2

[ 9] .gnu.version_r VERNEED 0804827c 00027c 000020 00 A 7 1 4

[10] .rel.dyn REL 0804829c 00029c 000008 08 A 6 0 4

[11] .rel.plt REL 080482a4 0002a4 000018 08 A 6 13 4

[12] .init PROGBITS 080482bc 0002bc 000030 00 AX 0 0 4

[13] .plt PROGBITS 080482ec 0002ec 000040 04 AX 0 0 4

[14] .text PROGBITS 08048330 000330 00017c 00 AX 0 0 16

[15] .fini PROGBITS 080484ac 0004ac 00001c 00 AX 0 0 4

[16] .rodata PROGBITS 080484c8 0004c8 000015 00 A 0 0 4

[17] .eh_frame PROGBITS 080484e0 0004e0 000004 00 A 0 0 4

[18] .ctors PROGBITS 08049f0c 000f0c 000008 00 WA 0 0 4

[19] .dtors PROGBITS 08049f14 000f14 000008 00 WA 0 0 4

[20] .jcr PROGBITS 08049f1c 000f1c 000004 00 WA 0 0 4

[21] .dynamic DYNAMIC 08049f20 000f20 0000d0 08 WA 7 0 4

[22] .got PROGBITS 08049ff0 000ff0 000004 04 WA 0 0 4

[23] .got.plt PROGBITS 08049ff4 000ff4 000018 04 WA 0 0 4

[24] .data PROGBITS 0804a00c 00100c 000008 00 WA 0 0 4

[25] .bss NOBITS 0804a014 001014 000008 00 WA 0 0 4

[26] .comment PROGBITS 00000000 001014 000023 01 MS 0 0 1

[27] .shstrtab STRTAB 00000000 001037 0000ee 00 0 0 1

[28] .symtab SYMTAB 00000000 0015d8 000410 10 29 45 4

[29] .strtab STRTAB 00000000 0019e8 0001fd 00 0 0 1

Name- is obtained by reading the value of the section names table at the specified indexTypePROGBITS- information that is given meaning by the program when loaded into memoryNOBITS- similar toPROGBITSin meaning but occupies no space in the fileSTRTAB- contains the program string tableSYMTAB- contains the symbol tableDYNAMIC- holds information necessary for dynamic linkingDYNSYM- holds a set of symbols used in the dynamic linking processREL- holds relocation entries

Addr- if the section is part of an executable it will hold the virtual address where the section could be found in memory. If not it would be 0.Off- offset from the beginning of the file to where the section startsSize- size of the section in bytesES- size in bytes per entry, if fixed entry size is usedFLGX- contains executable codeW- contains writable codeA- will be loaded into memory as-is during process executionAl- section alignment constraints

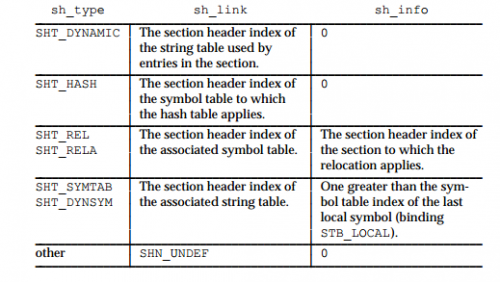

The Inf and Lnk columns have specific interpretations depending on the section type, as can be seen in the following image:

Additionally, the raw contents of each section can be dumped using both objdump and readelf.

readelf -x .got program

Hex dump of section '.got':

0x08049ff0 00000000 ....

objdump -s -j ".got" program

program: file format elf32-i386

Contents of section .got:

8049ff0 00000000 ....

For more details about the kind of data stored by ELF sections, refer to this resource.

When trying to dump contents of section using readelf you can interpret the output like strings by using the -p flag.

Symbol Table

One of the initial goals of the ELF format was to enable dynamic linking. Given the machine code of a binary, various elements inside it will use absolute addresses that are based on the memory address where the binary expects to be loaded. The entire idea of shared libraries is that these can be loaded and unloaded on demand inside the memory space of whichever process needs them at whichever address is available. As such, a map of how to locate and relocate absolute data points inside the machine code is needed and that's where the symbol table comes in.

readelf -s libtesting.so.1

Symbol table '.dynsym' contains 8 entries:

Num: Value Size Type Bind Vis Ndx Name

0: 00000000 0 NOTYPE LOCAL DEFAULT UND

1: 00001339 1 OBJECT GLOBAL DEFAULT 12 cPub

2: 000001f8 10 FUNC GLOBAL DEFAULT 7 fPub

3: 0000020c 100 FUNC GLOBAL DEFAULT 7 foo

4: 00001328 16 OBJECT GLOBAL DEFAULT 11 a

5: 00001338 0 NOTYPE GLOBAL DEFAULT ABS __bss_start

6: 0000133c 0 NOTYPE GLOBAL DEFAULT ABS _end

7: 00001338 0 NOTYPE GLOBAL DEFAULT ABS _edata

Symbol table '.symtab' contains 27 entries:

Num: Value Size Type Bind Vis Ndx Name

0: 00000000 0 NOTYPE LOCAL DEFAULT UND

1: 000000b4 0 SECTION LOCAL DEFAULT 1

2: 000000e8 0 SECTION LOCAL DEFAULT 2

3: 00000168 0 SECTION LOCAL DEFAULT 3

4: 000001a8 0 SECTION LOCAL DEFAULT 4

5: 000001d0 0 SECTION LOCAL DEFAULT 5

6: 000001d8 0 SECTION LOCAL DEFAULT 6

7: 000001f8 0 SECTION LOCAL DEFAULT 7

8: 00001274 0 SECTION LOCAL DEFAULT 8

9: 00001314 0 SECTION LOCAL DEFAULT 9

10: 00001318 0 SECTION LOCAL DEFAULT 10

11: 00001328 0 SECTION LOCAL DEFAULT 11

12: 00001338 0 SECTION LOCAL DEFAULT 12

13: 00000000 0 SECTION LOCAL DEFAULT 13

14: 00000000 0 FILE LOCAL DEFAULT ABS libtesting.c

15: 00000202 10 FUNC LOCAL DEFAULT 7 fLocal

16: 00001338 1 OBJECT LOCAL DEFAULT 12 cLocal

17: 00001318 0 OBJECT LOCAL HIDDEN ABS _GLOBAL_OFFSET_TABLE_

18: 00000270 0 FUNC LOCAL HIDDEN 7 __i686.get_pc_thunk.bx

19: 00001274 0 OBJECT LOCAL HIDDEN ABS _DYNAMIC

20: 00001339 1 OBJECT GLOBAL DEFAULT 12 cPub

21: 000001f8 10 FUNC GLOBAL DEFAULT 7 fPub

22: 0000020c 100 FUNC GLOBAL DEFAULT 7 foo

23: 00001328 16 OBJECT GLOBAL DEFAULT 11 a

24: 00001338 0 NOTYPE GLOBAL DEFAULT ABS __bss_start

25: 0000133c 0 NOTYPE GLOBAL DEFAULT ABS _end

26: 00001338 0 NOTYPE GLOBAL DEFAULT ABS _edata

Some information on the symbols that may belong to external files or may be referenced by external files during dynamic linking are copied in the .dynsym section.

Name- symbol nameTypeNoType- not specifiedFUNC- the symbol influences a functionSECTION- associated with a sectionFILE- a symbol that references a files

BindLOCAL- the symbol information is not visible outside the object fileGLOBAL- the symbol is visible to all the files being combined to form the executable

Size- the size of the symbol in bytes or 0 if it is unknownNdxUND- unspecified section referenceCOM- unallocated C external variableABS- an absolute value for the referencevalue- an index into the section table

Value- if the symbol table is part of an executable, the value will contain a memory address where the symbol resides. Otherwise it will contain an offset from the beginning of the section referenced byNdxorO

As you can see, the symbol table as it appears in object files compiled with gcc is quite verbose, revealing function names and visibility as well as variable scopes, names and even sizes. In its default form it even shows the name of the source file.

In order to subvert Reverse Engineering attempts you can check out some of the methods of stripping the symbol table of valuable information:

Relocations

Relocations were a concept that was present ever since the invention of static linking. The initial purpose of relocations was to give the static linker a roadmap when combining multiple object files into a binary by stating:

- The Symbol that needs to be fixed.

- Where you can find the symbol (file/section offset).

- An Algorithm for making the fixes.

The fixes would usually be made in the .data and .text sections and everything was well.

Dynamic runtime brought a bit of a complication to modifications that needed to be made in the code segments.

The whole idea of shared libraries is that the code can be loaded once into memory from an ELF file then shared among all the processes that use the library.

The only way to reliably do this is to make the code section read-only.

In order to compensate for this constraint a special data section called the GOT (Global Offset Table) was created.

When the code needs to work with a symbol that belongs to shared object, in the code entry for that symbol uses addresses from the GOT table.

First time the symbol is referenced the dynamic linker corrects the entry in GOT and on subsequent calls the correct address will be used.

When implementing calls to subroutines in shared objects, a different table is used called the PLT (Procedure Linkage Table).

The initial call is made to a stub sequence in the PLT which bounces off a GOT entry in order to push the subroutine name on the stack and then calls the resolver (mentioned in the INTERP program header).

Relocations and how they get applied are very complex topic and we will only try to cover as far is helps detecting file and symbol types If you want to read more you can refer to some of these resources:

readelf -r libdynamic.o

Relocation section '.rel.text' at offset 0x5f8 contains 8 entries:

Offset Info Type Sym.Value Sym. Name

0000001d 00001402 R_386_PC32 00000000 __i686.get_pc_thunk.bx

00000023 0000150a R_386_GOTPC 00000000 _GLOBAL_OFFSET_TABLE_

00000029 00000409 R_386_GOTOFF 00000000 .bss

0000002f 00000409 R_386_GOTOFF 00000000 .bss

00000035 00000d03 R_386_GOT32 00000004 so_int_global

00000041 00000d03 R_386_GOT32 00000004 so_int_global

00000052 00000e04 R_386_PLT32 00000000 so_fpublic_global

0000005b 00000209 R_386_GOTOFF 00000000 .text

Relocation section '.rel.data.rel.local' at offset 0x638 contains 2 entries:

Offset Info Type Sym.Value Sym. Name

00000000 00000401 R_386_32 00000000 .bss

00000004 00000201 R_386_32 00000000 .text

Relocation section '.rel.data.rel' at offset 0x648 contains 2 entries:

Offset Info Type Sym.Value Sym. Name

00000000 00000d01 R_386_32 00000004 so_int_global

00000004 00000e01 R_386_32 00000000 so_fpublic_global

Offset- In relocatable files and linked shared objects it contains the offset from the beginning of the section , where the relocation needs to be appliedInfo- This field is used to derive the index in the symbol table to the affected symbol as well as the algorithm needed for fixing.info >> 8- symbol table indexinfo & 0xff- algorithm type as defined in the documentation

readelf is nice enough to interpret the symbol table for us and gives us the relocation algorithm in the Type field and also the symbol name and value as defined in the symbol table.

By looking at the types of relocations we can draw some basic conclusions about the symbol types and also about the files.

- Relocatable Files

R_386_32- usually used to reference changes to a local symbolR_386_PC32- reference a relative distance from here to the symbol

- Relocatable Files for Shared object

R_386_GOTOFF- usually found in the code area, describes the offset from the beginning ofGOTto a local symbolR_386_GOT32- also specific to the code area. These entries persist in the linkage phaseR_386_PLT32- used when describing calls to global subroutines. when the linker will read this information it will generate an entry in theGOTandPLTtablesR_386_GOTPC- used in function to calculate the start address of theGOT

- Executables that use Dynamic Linking

R_386_JMP- the dynamic linker will deposit the address of the external subroutine during executionR_386_COPY- the address of global variable from shared object will be deposited here

- Shared Object Files

R_386_JMP- the dynamic linker will deposit the address of the external subroutine from one of the shared object dependencies during executionR_386_GLOB_DATA- used to deposit the address of a global symbol defined in one of the shared object dependenciesR_386_RELATIVE- at link time all theR_386_GOTOFFentries are fixed and these relocation will contain absolute addresses

IMPORTANT: Executable files that are statically linked do not contain relocations.

Challenges

Challenges can be found in the activities/ directory.

01. Binary Puzzle

Now that you know some stuff let's see how fast you can solve a 4 piece puzzle!

You are given 4 relocatable object files. Examine their structure carefully and figure out what each of them is meant to be and how you can link them to create a valid binary.

All conventions regarding shared object names have been respected.

Hints:

- Use

nmto investigate the files, determine what pieces you need to put together and then link them withgcc. - Check whether the files are compiled for 32 bits or for 64 bits and use the proper

gcccommand.

If you do it correctly you will get an executable that you can run and get the following output:

Congratulations

extern var1 10 at 0x565fe020

extern var2 at 0x565fe030

extern var3 99 at 0x565fe024

local var4 0 at 0xffd532ac

g(): not really external

02. Case of the Missing Function

This task contains a helpless little binary that has lost one of its functions. Analyze the symbol dependencies as well as the code inside the binary. Figure out a way to reunite the binary with its missing function.

You cannot modify any of the binaries in order to solve this task.

Hints:

- Run the file, check what it is missing and build the missing component.

Use

nmto determine what symbols should be part of the missing component. - Use

LD_LIBRARY_PATH=.to run an executable file and load a shared library file from the current folder.

03. Memory Dump Analysis

Using your newfound voodoo skills you are now able to tackle the following task. In the middle of two programs I added the following lines:

{

int i;

int *a[1];

for( i = 0 ; i < 20; i++)

printf("%p\n", a[i]);

}

The results were the following, respectively:

0x804853b

0x1

0x8048530

(nil)

(nil)

0xf7e0ace5

0x1

0xffffce64

0xffffce6c

0xf7ffcfc0

0x1c

(nil)

0xf7fda4c8

0x2

0xffffce60

0xf7f94e54

(nil)

(nil)

(nil)

0xd545cf8d

And:

0xbfffe7d0

0xd696910

0x80484a9

0xb7fffbe8

0x3

0xb7ffefc0

0xb7df6a84

0x1

0xb7fdc780

0xb7fe75fc

0x804c008

0xb7e59195

0x804c008

0xb7fdb000

0xb7fdc000

0x1

0xffffffff

0x3

(nil)

0xf3b9a5b

Try to tell:

- Which was running on a pure 32 bit system?

- Which values from the stack traces are from the

.textregion? - Which do not point to valid memory addresses?

- Which point to the stack?

- Which point to the library/

mmapzone?

04. Compiler Flags

Use proper compiler/linker flags/options to create a running executable for flag1.o and caller.c and for flag2.o and caller.c.

Submit the flag on the platform.

It's the same flag, it's just to make sure you are able to find the flag with both formats of the flag*.o object files.

05. Print Flag

Someone has tampered with the executable file get_message.

Please fix this.

There should be a flag message printed in case you solve it correctly.

You will need to modify the executable. We recommend you install and use Bless.

What actions does the program do? What functions does it invoke? What should it invoke?

Follow the actions from the entry point in the ELF file and see what is the spot where the program doesn't do what it should.

06. matryoshka

Look carefully inside the matryoshka executable.

The flag is there, but inside something else.

Submit the flag on the platform.

Bonus: 07. Fix Me

You are given a binary that was stored on a USB stick in space where it was hit by gamma rays thus altering its content. Fortunately, because the executable is so small, the only area damaged is the ELF header. Fix it and run it!

The structure of an ELF file is briefly presented here

A more detailed explanation of the ELF header is presented here

The entry point address should be 0x8048054.

Review this tutorial on creating a minimal ELF file.

Further Pwning

This is a challenge that will test your knowledge from the first three sessions.

The password for the archive is crackmes.de.

Further Reading

- ELF-32

- ELF-64 specification

- list of all ELF specification formats

- ARM specification

- Position Independent Code

- Creating shared objects

GNU_RELROGNU_STACK- ELF Special Sections

A Whirlwind Tutorial on Creating Really Teensy ELF Executables for Linuxstripman page- Some Assembly Required

Study Of ELF Loading and Relocs